Revamping a Webquest

Earlier this week, Fordson science teacher Sarah Collada and I sent students on a traditional webquest to explore the phenomenon of water diversions in AP Environmental Science (affectionately known as “APES” to many). The webquest consisted of a document with multiple sections and questions for students to answer in order to complete each of the sections. The questions were pretty intense and asked for a lot of information.

However, as students began working, we noticed that all they had to do is google the exact question and the search returned the work of students who had done the webquest before and had published their answers online. Were they cheating? I’m not so sure. After all, we were asking them to search for answers online–and that’s exactly what they did. Were they cheating themselves in the long run? That’s more likely. But not because they were finding answers. What we observed was that students were simply writing down the first thing they saw. And, in some cases, even though what they were writing was directly from a document that looked like the one they needed to respond to, the answers were different from those found by others. Nevertheless, they were going to stick with what they found first.

In discussing this phenomenon, Sarah and I began to explore some other options. First of all, the webquest was truly focused on knowledge the students needed to acquire. But the mindless activity of, as Mrs. Collada calls it, “copying symbols” is not going to get it done. Furthermore, what students were doing showed not only a misunderstanding of what learning is, but also a misconception about how the internet really works. And that’s not to mention the fact that students believed it was perfectly ok to copy down another person’s work and pass it off as their own.

Answers are everywhere

The fact of the matter is, as Sugata Mitra says, “answers are everywhere”. Students in the 21st century need to appreciate that the one thing they don’t lack is answers. What they do lack, however, is the skill in discerning which answers are correct and which answers best address the questions they are trying to ask. In fact, one of the most important skills students need to learn today is how to ask the right questions.

Here’s the thing: if we (teachers) are the ones asking the questions, then students aren’t. And if students can answer our questions with a quick Google search, we need to change the questions we ask and the way we ask them.

What Sarah and I decided was that what is most valuable in a situation like this is that students a.) recognize that there are multiple answers from multiple sources with varying degrees of credibility, and b.) that they do their own work. The best way for students to really interact with the content was to find answers, lay them on top of each other, distill out what was true and relevant, and discard the rest. Even more, we decided they needed to synthesize their own answers from the information they found and give credit where credit was due by citing their sources.

Our expectations of kids with technology need to reflect what they can actually do.

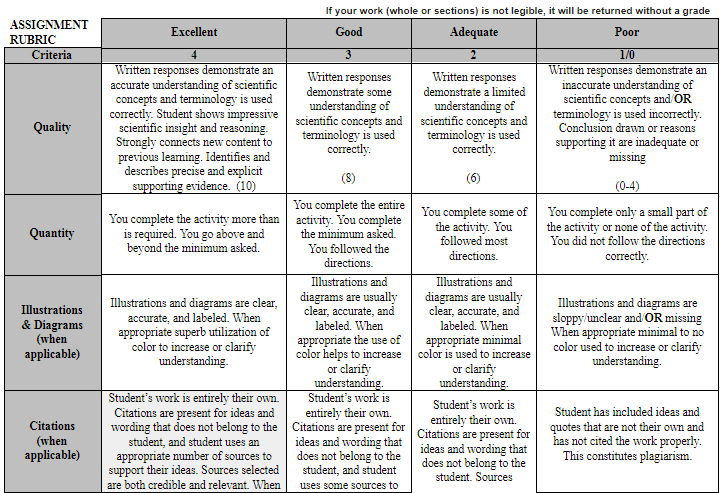

We began by revisiting the rubric used for assignments such as this one using the collaborative nature of Google Docs and the Commenting and Suggesting features. Our discussion centered on how we would know that they knew what they were supposed to, and how they might show their understanding. While it may not be perfect, we made some progress on our rubric in showing the value of some of these aspects of learning.

Changing the game

Next, we began to look at how to change the activity itself so it reflected the way we wanted students to collect and process the information and then synthesize their own work. Here’s what we’ve come up with so far…

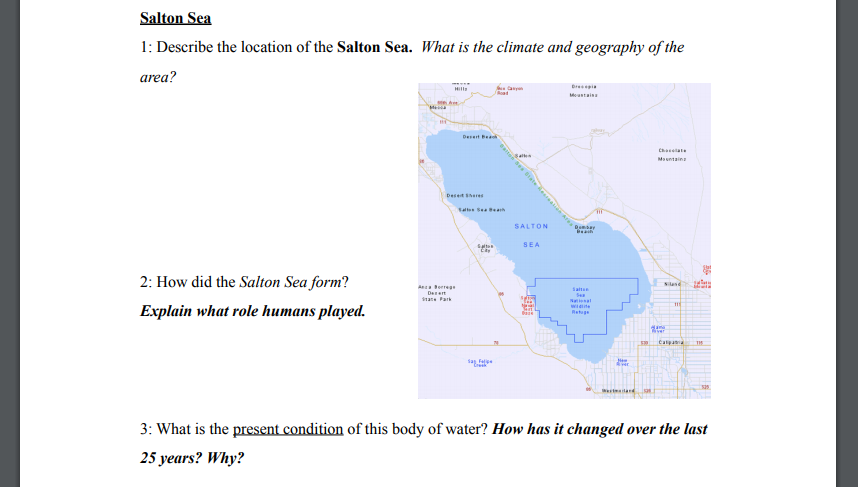

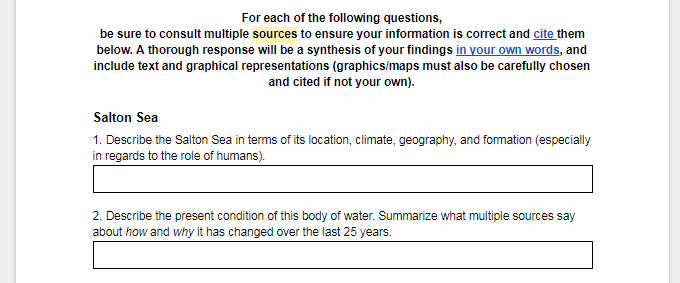

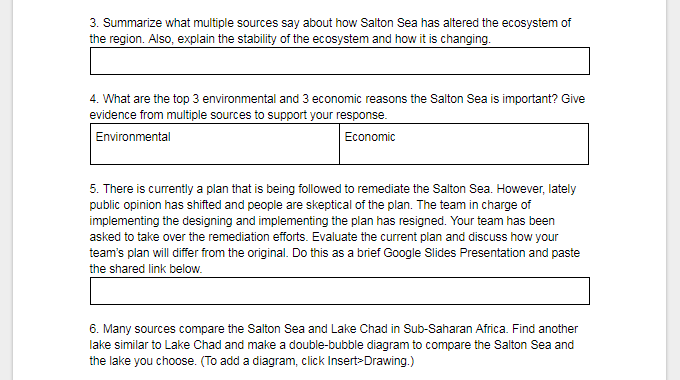

The original:

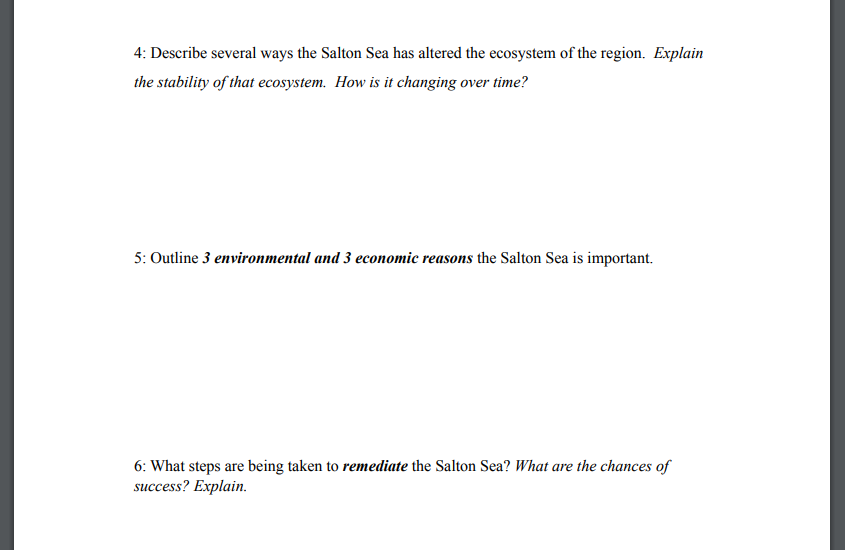

The revised edition:

Note that the revised edition is a Google Doc instead of a PDF, which contains self-expanding tables for students to be able to enter their answers, and it contains links to EasyBib to assist students in citing the work (because our goal is definitely not to have students spend as much time trying to figure out how to cite the sources as finding the sources themselves), as well as a link to plagiarism.org to help them understand the value of doing their own work. It also re-words the questions so as to describe what we are looking for, but allows the students to actually ask the questions.

Easybib Destination URL: https://www.easybib.com/